ShapeShift Hack: intertwining thefts & multi-year mixing

The Background

Between March and April 2016 Switzerland-based cryptocurrency exchange ShapeShift suffered three separate hacks resulting in the loss of around $230,000 in cryptocurrency. The information was first made public as part of an incident report obtained by CoinDesk.

ShapeShift CEO Eric Vorhees gave several interviews in which he described in detail the events leading up to the hacks and how they were dealt with internally.

The first hack of BTC 315 ($130,000) was carried out on 14 March 2016 by an employee who later allegedly sold key security data to an outside hacker, including access details for the exchange’s admin interface. Voorhees disclosed this in a memo to ShapeShift users on 13 April.

That hacker then carried out two separate attacks on 7 and 9 April 2016 that led to the loss of a further BTC 164, ETH 5,800, and LTC 1,900 ($100,000). No customer funds were lost.

By all accounts the funds were never recovered. But the movement of stolen funds continued for a further three years.

Mixing The Funds

Much of the reporting on the initial hack - including the postmortem in which Voorhees discussed at length his interaction with the insider - has now been removed. But some reporting still remains.

We used this article (written by Voorhees himself) as a starting point. It provides the address to which the stolen BTC 315 was first sent: 1LchKFYxkugq3EPMoJJp5cvUyTyPMu1qBR.

Immediately, we see a peeling chain - a series of transfers in which small portions of funds are systematically siphoned off into newly created addresses.

Peeling chains make tracing more problematic given the potential to distribute funds across hundreds of addresses. We counted 248 addresses in the main peeling chain, and many more in side chains.

The most notable feature of these first transfers is that the hacker used Helix, a Bitcoin mixing service which operated from 2014 until 2017, as the primary destination of peeled funds. As shown below, this began with BTC 1 to Helix on 30 June 2016.

Helix allowed customers to send Bitcoin in a manner that was designed to conceal the source (or owner) of the funds, in return for a fee. It was closed in 2020, as explained in Hoptrail’s synopsis of the hack:

On 13 February 2020, the US Department of Justice (“DoJ”) announced that it had charged the operator of Helix, US national Larry Harmon, with conspiracy to launder illicit proceeds, operating an unlicensed money transmitting business and conducting money transmission without a District of Columbia license. The DoJ alleged a link between Harmon and darknet search engine Grams, on which Harmon supposedly marketed Helix. It was estimated that Helix had mixed over 350,000 Bitcoin on behalf of customers, the majority of which originated from dark web marketplaces.

Stolen funds continued to be deposited to Helix until its closure. In late 2020, the hacker switched to Wasabi Wallet, a non-custodial wallet featuring a coin mixer utilising 'CoinJoin', which amalgamates clusters to hide the source and destination of the funds.

This continued until 8 November 2020 when the final deposit in the chain was made to Wasabi. In all, it took the hacker three and a half years to eventually dispose of the stolen funds through mixers.

Identifying Other Services

Transaction analysis shows the hacker was primarily siphoning off Bitcoin to mixers in small chunks, typically BTC 1. However, in some cases larger amounts were separated. In a few of those, centralised services were identified.

In May 2019 hacker sent funds to Changelly, an exchange aggregator. Changelly differs from other exchanges by operating as a non-custodial market participant, meaning that it does not hold users’ funds on the platform. Rather, it acts as an intermediary between crypto exchanges and users. Currently, users are only required to undergo identity verification if their transactions are flagged as suspicious by the exchange.

In another instance on 6 May 2020, we see BTC 1 deposited to MorphToken, another peer-to-peer service that does not require user verification.

What does this show? The hacker is clearly seeking ways to off-ramp their funds using exchange services that do no require KYC.

But the trail leaves additional information that might reveal where and how the hacker sought to off-ramp other proceeds; and, intriguingly, information suggesting the separate hacks of ShapeShift are in fact connected.

Centralised Exchanges and Other Illicit Proceeds

Two days after depositing to MorphToken, funds stolen from ShapeShift were sent to Huobi. In total, the hacker deposited almost BTC 7 to the Huobi deposit address over a two day period.

This is where it gets interesting.

The same Huobi address has received a significant amount of Bitcoin from MorphToken - over BTC 4,400 between April and December 2020.

Hoptrail’s analysis of the Huobi wallet shows that it received funds from MorphToken across 14,918 inputs in eight months - all in sizes of less than BTC 1. This pattern suggests mixing may have been deployed to obscure the origin of the funds.

In total the Huobi wallet received £39.3 million, which includes funds from a series of unknown clusters - all for the same amount, and all during late 2020.

This is indicative of a larger theft.

Are these funds part of the second spate of attacks on ShapeShift? It is possible that ETH and LTC were converted into BTC on MorphToken before hitting Huobi.

The answer will lay in who controls the Huobi account.

Crypto HNWIs: who they are and how they made their wealth

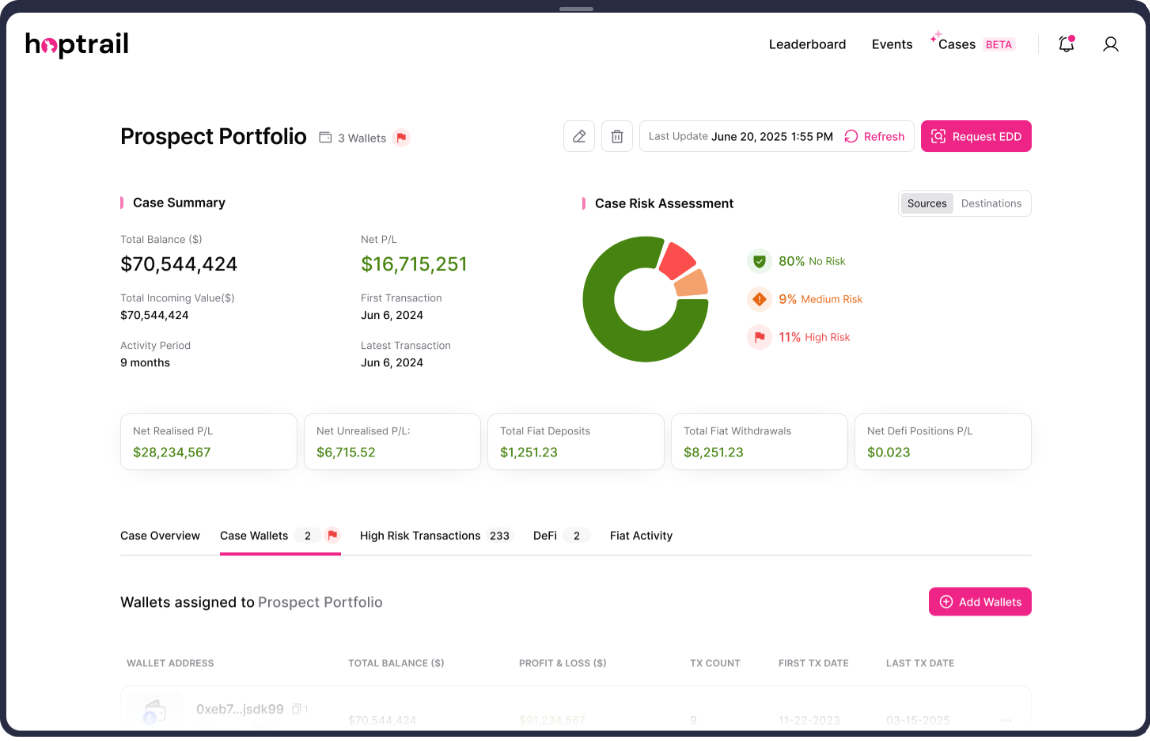

Cases: new source of wealth capabilities and upcoming features

Why we built Cases: A personal note on solving the crypto source of wealth headache

Subscribe to the Hoptrail newsletter

Sign up with your email address to get the latest insights from our crypto experts.